The Seals of the Order of the Temple

Inherited from Antiquity, the use of the seal reached its apogee in the 13th century, spreading, on the fringe of the development of the written word, throughout medieval society. The wax imprint, affixed at the bottom of a charter, commits its holder and guarantees the integrity of the content. Beyond this function, the seal is also the main communication tool of the medieval world. Formed around a synthetic iconography, it proclaims the identity of the signatory and conveys the emblematic image created by the latter and by means of which he wishes to be recognised.

Shortly after its adoption by the great lay feudatories, the seal was imposed at the beginning of the 12th century for the management of monastic establishments, committing both the abbot as its representative and the community, as a moral authority, and, as such, provided with a matrix. Only the Order of Cîteaux, initially very cautious about this new instrument, imposed on all its abbeys the use of an anonymous and unique matrix for the abbot and his community.

Although the first documented imprint of the seal of the Order of the Temple dates only from 1167, it may have possessed a matrix from the very first years of its existence. It is nevertheless established that in 1147 Évrard des Barres affixed the seal of the Grand Master at the bottom of a private deed notifying a donation made by his nephews to Saint-Victor de Paris and therefore not binding on the entire community.

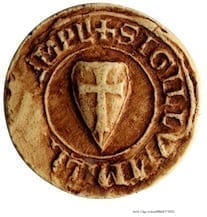

In its early days, the Order of the Temple only used a single seal, the ball, a double silver matrix designed on the model of the Byzantine-inspired bullae used throughout the Mediterranean basin and in particular by the popes and kings of Jerusalem. On the first side appears the famous representation of the two brothers in arms on the same horse (ill. 1), a double allegory of the humility of the brothers and their solidarity, two virtues claimed from the beginning by the Rule. This seal, which was renewed several times, will remain the most stable and most perfectly representative model of Templar identity until the trial. On the reverse side, a particularly realistic design shows a dome topped by a cross and supported by an arcaded gallery. This figuration uses an encoding well known from medieval images, the symbolism of the part for the whole: the Dome of the Rock is both the first of the commanderies and the headquarters of the order of the Temple and remained so after the fall of the Holy City in 1187 and the transfer of the order’s headquarters to Acre (ill. 2). The legend, which begins on one side – + SIGILLVM: MILITVM – and continues on the other – + DE TEMPLO: CRISTI -, makes the two elements inseparable.

Following the example of the gonfanon baucent, the use of this seal is strictly codified, almost sacralized, by several articles in the retreats of the Rule, in particular the hierarchical statutes attributed to Bertrand de Blanquefort, Grand Master from 1156 to 1169. Preserved in a leather purse, the ball is a double silver matrix. A Templar who has been guilty of violence against another may not touch it (“If a brother puts his hand, with anger and wrath, on another brother (…), he may not wear the gonfanon baussant, nor the silver ball”, art. 234). The same punishment is reserved for a Templar who has traded with a woman (“If it is proved that a brother has slept with a woman, the habit cannot be left to him and he must be put in irons. And he may never wear the gonfanon baussant, nor the ball”, art. 452) or to the one who has broken the ball, even inadvertently (“And our old men say that if brothers break the ball of the one who would be in the master’s place, the habit could be taken away from them for the same reason, so ugly is the fault and for the damage that could occur”, art. 459).

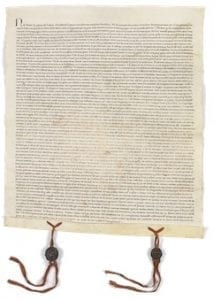

The creation of the Cismarine visitor’s office in 1164 led to the duplication of the seal of the order. The Grand Master kept the reverse side of the ball, the tube, which owed its name to the distortion of the word kuba – the dome – and the visitor took the obverse with the two horsemen for his own use. A first example is offered around 1190 by Gilbert Erail, cistra marinorum humilis procurator, at the bottom of an agreement between the Templars of the Bure commandery and the monks of Grancey. It seems, however, that the Grand Master exceptionally continued to seal the two horsemen, as can be seen from the examples of Pierre de Montaigu, validating an agreement with the Hospitallers in 1221, and Guillaume de Beaujeu, sealing as a witness an act of Henry II of Lusignan, King of Cyprus and Jerusalem, of 1286. On the other hand, it may happen that the Grand Master may combine his office with that of cismarine visitor when the latter is vacant, the retreats expressly requesting that upon the death or replacement of the latter, his womb be immediately returned to the Grand Master (art. nos. 88 and 579). The case appears to occur with Renaud de Vichier, sealing both as Grand Master of the Order and visitor during the settlement of the dispute between the Knights Templar and the Count of Champagne in July 1255 (ill. 3).

The provinces and commanderies also have a community seal. In Paris, the seal of the commandery, head of the province of France, was renewed before 1290: in a four-sided quatrefoil with red teeth is a flowered cross, surrounded on the left by a very faithful image of the dungeon of the Temple of Paris, recognizable by its corner turrets, and on the right by a Templar friar, probably the master of the Temple of Paris, kneeling in prayer (ill. 4). This example confirms an engraving of rather fine quality, the work of a Parisian goldsmith accustomed to these frames and to the almost realistic representation of the emblematic monument of the Parisian commandery. The model is preserved by the Order of the Hospital as early as the 1330’s. Other commandery seals are documented in the years before the arrest or, in 1308, when the brothers of Aragon locked themselves inside their fortresses. In the kingdom of Aragon, as in Vaour, in the south of Languedoc, these seals reproduce without exception the model of the castle with three towers, symbolising these fortresses, which appears as the true prototype of the power of command in many administrative seals of the Middle Ages (ill. 5). Just these fortresses are distinguished by the addition of distinctive signs such as animal supports (greyhounds in Monzon), sometimes speaking (bars in Barbera), a summit cross (Peria) or astral decorations (Vaour).

The dignitaries of the Order, from the Grand Master to the holder of a command or office, may possess a seal as part of their function. This is the case of the masters of the provinces, tutors, certain chaplains, treasurers or commanders who develop a varied iconography, mitigated, however, by the concern of the provinces to adopt a visual code that allows a quick identification of their seals: tower of the Temple of Paris (France), cross pattée (Poitou, ill. 6), head of a bearded man (Hungary), Agnus Dei (Provence, England and Aragon, ill. 7).

Some dignitaries may also make use of a personal matrix. The practice, which is quite rare, is reported in 1286 when Guillaume de Beaujeu affixed his own seal, to the arms of his lineage (a lion), as a counter-seal to the tube. The matrix of Pierre Péllicier, chaplain of the Temple at the beginning of the 14th century (ill. 8), one of the few preserved, reproduces the Christic theme of the pelican tearing its entrails to feed its young, while making a play on words with the name of the dignitary. The seal of Jean de Tour l’Aîné, treasurer of the Temple of Paris between 1274 and 1302, is interesting because it testifies both to the use of these talking emblems and to the vogue for engraved stones set in seal matrices since the end of the 12th century. Documented by an imprint of 1295, this object is decorated with an oval intaglio representing an eagle holding a crown in its beak, which in turn is flanked by two towers and surrounded by an orle of fleurs-de-lis. Another famous stone is the one embedded in the matrix of the seal of secrecy (understood as a private seal) of the Master of France and engraved with an Abraxas, a fantastic figure representing a rooster’s head on a bust of a man carried by snake legs (ill. 9). Far from the esoteric interpretations to which it has given rise, this intaglio shows the fascination of the Crusaders for these stones endowed with therapeutic and prophylactic virtues that they brought back with them from their numerous journeys to the East.

Finally, other sigillar images are a sign of the personal devotion of the order’s dignitaries, such as the one used by William of Gonesse, Templar commander of the Passage (magister passagii), around 1255 (ill. 10). This dignitary, based at the commandery in Marseilles, was responsible for transporting material and men between the West and the East. This small round seal (25 mm) and anepigrapher depicts Saint George on horseback, slaying the dragon. Of an archaic style, this seal cannot be linked to the classical Western models of the 12th and 13th centuries. The disproportion between the head and the rump of the horse, the unusual gait of the rider, the features of the design increased by the asymmetrical grooves of the monster and the stars in the field are all characteristics that make the engraving look like an intaglio. This is clearly a seal for private use of oriental inspiration, perhaps a sigillar ring within which, once again, a stone purchased in the Holy Land has been set, endowed in the eyes of its owner with a number of virtues, including that of protecting him during his frequent crossings of the Mediterranean.

The seal matrices of the Order and the dignitaries were confiscated from the Temple of Paris by the men of William of Nogaret on 13th October 1307, as were those of the French commanderies on the same day. Symbols of the legal capacity of the institution, most of them were destroyed after the disappearance of the order in 1312. And with them a whole catalogue of images, far more numerous than those preserved today, which were as many testimonies of the spirituality of these men, expiatory victims of a conflict that had overtaken them.

Arnaud Baudin

Deputy Director of Archives and Heritage of the Aube – LAMOP (UMR 8589)

Two riders on the same horse

Moulding of the obverse of the ball of the Order of the Temple (1259)

Paris, Arch. nat. sc/D 9863

The Dome of the Rock

Moulding of the seal of the great master (1255)

Paris, Arch. nat. sc/D 9862

Agreement between the Grand Master Renaud de Vichier and the Count of Champagne Thibaud V concerning the property of the Order of the Temple in Champagne (July 1255). The deed is sealed with the visitor’s ball and the seal of the Grand Master.

Paris, Arch. nat., J 198B, n° 100

The Tower of the Temple of Paris

Moulding of the seal of the commandery of the Temple of Paris (1290)

Paris, Nat. arch. sc/D 9915

Castle with three towers

Moulding of the seal of the commandery of Vaour (1303)

Paris, Arch. nat. sc/D 9876

Cross pattée

Moulding of the seal of the Master of Poitou (1302)

Nat. archivist, sc/E 1663

Agnus Dei

Moulding of the seal of Raimond de Caromb, preceptor of the Temple in Provence (around 1251)

Paris, Arch. nat., sc/St 154

Pelican tearing its entrails to feed its young

Matrix of the seal of Peire Pellicier, chaplain of the Temple (1308)

Paris, Bibl. nat. Fr., cat. 260

Abraxas intaglio

Moulding of the seal of the secret of the Master of France (1259)

Paris, Nat. arch. sc/D 9863bis

Saint George slaying the dragon

Moulding of the seal of Guillaume de Gonesse, Templar commander of the Passage (1255)

Nat. arch. sc/B 1558